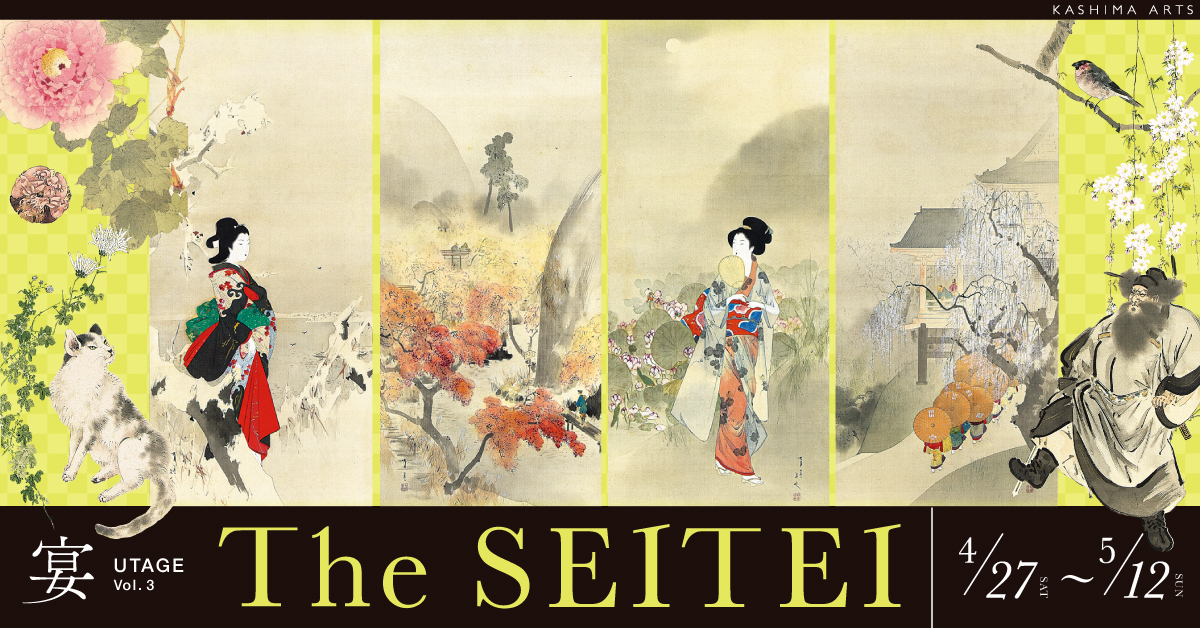

A triptych, color on silk, with a box signed and sealed by the artist

111×35cm / 192×45cm

vol.25 The Eye of a Crane and the Eyes of Marie Thérèse: Cranes, Pine, Bamboo and Plum

The Japanese Crane (Grus japonensis) are widely known in Japan as celebratory, auspicious birds. Their body is as white as snow, while their face, neck, and a part of wings (secondary and tertiary flight feathers, the latter is often confused with the tail) are black. Their most notable feature is the red crown on the top of their heads (which actually is exposed skin). Their body length spans 140cm (from the tip of their beak to the end of their tail) and, when including their long legs, they are as large as a male human adult. They are well known historically and hold outstanding name recognition. When thinking of cranes, the Japanese Crane, not the White-naped Crane (as mentioned in Vol.22,) would generally be everyone’s first thought. A popular symbol of longevity and a harmonious marriage, paintings of Japanese Cranes were in high demand, as auspicious and celebratory items. Without a doubt, the Japanese Crane takes a leading part in bird-and-flower paintings.

Naturally, the bird-and-flower painter, Seitei, has painted the Japanese Crane. Nevertheless, there are surprisingly only a few examples of this that I can identify, such as “Birds and Flowers of the Twelve Months: January” (Private Collection) and “Cranes” (Saita Memorial Museum). Even amongst these works, this work, a triptych with two splendid Japanese Cranes in the central scroll, is a masterpiece. With this, I would like to discuss how Seitei paints Japanese Cranes.

Generally, Seitei is close to perfect in his depiction of the Japanese Crane’s body and legs. In a certain television show, an expert stated that “the quality of a bird-and-flower painting can be determined by the depiction of the bird’s legs,” and I could not agree more. Especially because the crane’s legs are so long and distinct, there is no exaggeration in stating that the legs are the life of a crane painting. The real legs of a Japanese Crane are thick and strong, and their bones are raised around their joints (the part that corresponds to their heels). The three toes facing the front are long, while the one toe facing backwards is small and barely touches the ground. Furthermore, their legs are covered in scales, which are generally consistent in shape and alignment between species. With Japanese Cranes, large scales run in the front from the base of their toes to their joints, while medium scales forming a line behind, and small vertical scales line up on the left and right sides. Additionally, small scales also scatter above their joints (the part that corresponds to the shin). As such, a realistic depiction of a Japanese Crane’s legs depends on how accurately the shapes and composition of their scales are captured but, needless to say, Seitei’s depiction is perfect.

On the other hand, these cranes’ faces are rather unique and, so to speak, ornithologically incorrect. Firstly, their beaks are too long and span 1.5 longer than the real thing. Moreover, evidently, the positioning of their eyes is very odd. The crane in the foreground looks fine. Yet, the eye of the crane standing diagonally behind is considerably deep-set. To examine, I moßved one eye forward. With this, its appeared normal and the work no longer seemed unbalanced. Now, I understand why Seitei’s depiction looked so unnatural and unbalanced.

This oddly positioned eye completely dominates its expression and overwhelms the impression of the work. So why did Seitei position its eye incorrectly? I can think of two possibilities. The first is just a mistake. Any genius is susceptible to errors, therefore it is perfectly possible for someone like Seitei to mistakenly position a bird’s eyes. However, would Seitei have allowed such an imperfect work to remain in the world? Many artists would never allow a work with such obvious flaws to continue existing. As such, Seitei, too, must have torn, burned and destroyed his mistakes. If so, this work would not exist. However, an alternate explanation is that Seitei intentionally drew this eye in this position.

What was “Seitei’s intention” in painting the Japanese Crane’s eye in such an unusual position? Although it is difficult to assume his intent, perhaps it had something to do with this three-piece hanging scroll and its auspicious “Sho-Chiku-Bai” (lit. Pine, Bamboo and Plum) motif in its right and left scrolls. This “celebratory”-themed work would have been on display at auspicious events or at New Years. In Japan, there is a humorous face called “Fukuwarai” that is displayed during New Years. Perhaps, Seitei painted the eye oddly in reference to “Fukuwarai” to bring laughter at New Years. Moreover, inspired by the “Fukuwarai”, he may have attempted to make the work more three-dimensional by drawing the crane’s eye abnormally. It distorts the crane’s face, and gives a three-dimensional effect to the space around the face (albeit not necessarily successful…).

Painting an object as if its surrounding space was distorted. We, who live in modern times, are familiar with this idea. This innovative concept is the “Cubism” movement, which was established by Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), and later popularized by Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). With this in mind, when revisiting this work, I find the crane’s eye resembling the eyes of Picasso’s “Seated Woman (Marie-Therese)” (The Picasso Museum, Paris). Seitei (1851-1918) is a generation younger than Cezanne, and is much older than Braque and Picasso. Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was exhibited in 1907 and, although the dating of this work is unknown, it may have predated Picasso’s work. Perhaps this was Seitei’s attempt at Cubism that predated Picasso. Looking at its eyes, I feel the seeds of Cubist aesthetics in this work. While my assumption might be outlandish and exaggerated, every time I think about it, I feel excited.

Author : Masao Takahashi Ph.D. (Ornithologist)

Dr. Masao Takahashi was born 1982 in Hachinohe (Aomori prefecture) and graduated from Rikkyo University’s Graduate School of Science. Dr. Takahashi specializes in behavioral ecology and the conservation of birds that inhabit farmlands and wet grasslands. Focusing on the relation between birds and art, he has participated in various museum and gallery talks.