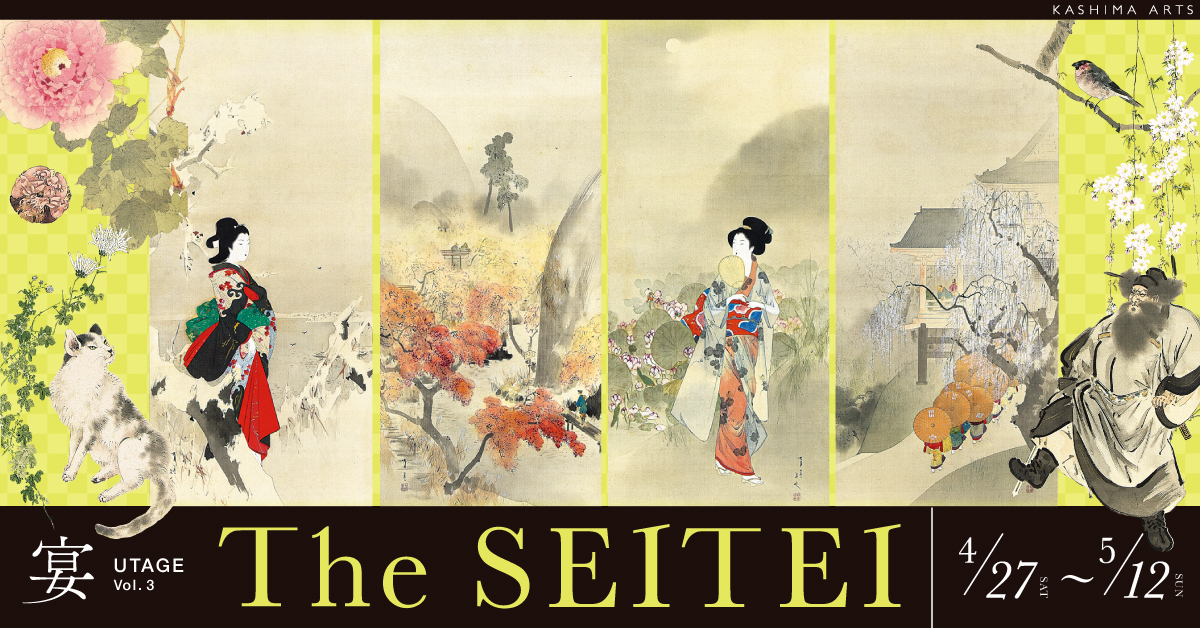

vol.26 The Bird That Changed Art: Bulbuls in Snow

The Brown-eared Bulbul (body length 27cm) is a common small bird. Their bodies are larger and slenderer than Tree Sparrows, and they have with grey (dull silver) feathers. Compared to their body size, their wings and tail are relatively large, and they have an unkempt crest, glowing and elongated black beaks and cute orange cheeks. They inhabit the forests of mountains and flatlands, and civic spaces with trees, such as parks, shrines, roadsides and gardens. Bulbuls sing, “hi-yo hi-yo” loudly and stand out for their exaggerated actions. They eat small insects and fruits, and have a considerable sweet tooth. They enjoy eating camellia and cherry blossom nectar, as well as apples, persimmons, oranges and other sweet fruit. They have fairly rough temperaments and drive other birds away to monopolize food.

The Brown-eared Bulbul has drastically changed its habitat in recent years. They used to breed in mountains and migrate to urban spaces only during the winter. In an old handbook of birds, the Brown-eared Bulbul is described as “winter birds in human settlements”. However, since the 1970s, they began to habituate urban spaces all year round, with many bulbuls now breeding in such areas as well. While typically conspicuous, bulbuls do not assert themselves much during the nesting season and are quiet parents that build small nests in tree groves around gardens or the roadside.

Despite being a common bird, Brown-eared Bulbuls do not feature often in Japanese paintings. Furthermore, while they might occasionally appear in bird-and-flower paintings with many birds, they are rarely the focus of the work. Perhaps their commonality, dull colours and difficult personality contributes to their lack of popularity, in the past and the present.

Seitei, however, went against the grain. This rare work focusses on the Brown-eared Bulbul, and its high detail ranks highly even amongst the Seitei’s oeuvre. Firstly, I would like to draw attention to its feathers. Its whites, greys and light browns are painted finely and contributes to the work’s overall colour composition. Although the real Brown-eared Bulbul is light brown, tips of their feathers are silver-grey and their roots, which is hidden by overlapping feathers, are white and fluffy. Seitei’s work faithfully reproduces the details of its true feather colours, as well as its body’s softness and flexibility. From its overlapping, white-edged feathers from its hips to the base of the tail, to the roughness of its crest, edges of its eyes and the protruding and slight downward bend of its upper beak, Seitei’s portrayal can be described as painfully accurate. So much as that it could be tentatively regarded as “the world’s best painting of a Brown-eared Bulbul”.

Like Seitei, Yoshimichi Fujimoto (1919-1992) is one of the few artists who gave the Brown-eared Bulbul a leading role. Fujimoto was an acclaimed ceramist of the later Showa period whose porcelain is highly valued for their unique overglaze enamel. He frequently depicts highly realistic bird-and-flower themes in his ceramics, often featuring birds common to Tokyo suburbs, such as the Common Kingfisher, the Bull-headed Shrike, the Daurian Redstart and the Japanese Tit. Beautiful and realistic, one would never suspect these works to be works of porcelain and overglaze enamel.

Let’s discuss the bulbul paintings of the Musée Tomo collection, which is famous for its Yoshimichi Fujimoto works. In “Sohaku and Yubyo Glaze Gold Leaf Hexagonal Box with a Brown-eared Bulbul Design”, a bulbul stands on a camellia tree, while in “Octagonal Box with Magnolia and Brown-eared Bulbul Design” a bulbul perches by a large magnolia flower. Both works depict early spring landscapes, so perhaps these bulbuls are in the search for nectar. With “Dodecagonal Plate with Cherry Blossom and Brown-eared Bulbul Design”, a bulbul eyes a red and ripe cherry in the green of early summer. Each work captures the habits of the sweet-toothed bulbul with ornithologically correct colours and anatomy.

.jpg)

Yoshimichi Fujimoto, “Sohaku and Yubyo Glaze Gold Leaf Hexagonal Box with a Brown-eared Bulbul Design”

H2.8 W26.2 D25.7

Kikuchi Collection Photo:Yasuhiro Ookawa

How do Seitei and Yoshimichi differ in their depictions of the bulbul? What I took notice of was their choice of seasons. While there are only a few works to reference, Seitei tends to depict bulbuls in winter, while Yoshimichi prefers early spring or early summer. During the Meiji period, when Seitei was an active painter, Brown-eared Bulbuls bred in the mountains and urban residents would see them only in winter. Naturally, Seitei painted bulbuls in snowy winter landscapes. On the other hand, Yoshimichi was active during the late Showa period, when bulbuls began to breed in urban areas. The three aforementioned works were produced in the 1970s and 1980s. As such, paintings of bulbuls would have been influenced by actual sightings of bulbuls in early summer and early spring.

If Brown-eared Bulbul bred in nearby urban areas earlier, then Seitei may have depicted them in green landscapes. On the other hand, if bulbuls still bred in mountains, Yoshimichi’s “Brown-eared Bulbuls of early summer” would never have been made. Changes in avian distribution and ecology has the potential to influence human art and culture. In other words, art works can reveal the background and history of painted birds. As such, ornithology and art theory may in fact be closely intertwined schools of thought.

Author : Masao Takahashi Ph.D. (Ornithologist)

Dr. Masao Takahashi was born 1982 in Hachinohe (Aomori prefecture) and graduated from Rikkyo University’s Graduate School of Science. Dr. Takahashi specializes in behavioral ecology and the conservation of birds that inhabit farmlands and wet grasslands. Focusing on the relation between birds and art, he has participated in various museum and gallery talks.