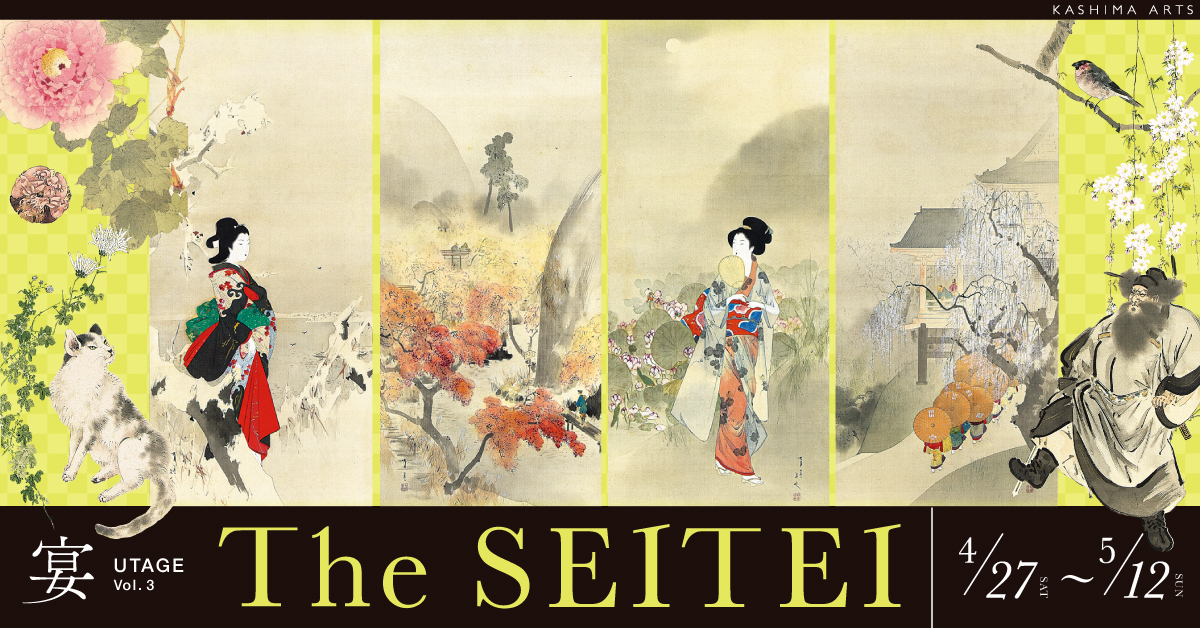

A pair of six-folding screens, color on gold-ground paper 173×174cm

vol.28 Reasons to be Alone, Reasons to be with Others: Folding Screen with Birds and Flowers

Birds live in flocks. From the pigeons that gather for food in front of stations, to the ducks in parks that float on ponds, sparrows that line up on power lines and crows that head to their roost in the evening; most birds we encounter in our surroundings live in groups. The sight of flocking birds filling the sky can produce feelings of awe however, it is a common occurrence in nature.

So why do birds live in flocks? Ornithologists have long struggled to answer this question from an ecological and behavioral perspective. Whether a bird even lives in a flock varies greatly depending on its species, season and circumstance. During the breeding season when egg-laying and chick-rearing begins, birds naturally begin living in pairs or families. As such, most flocks tend to be small, however, some birds, like gulls and cormorants, gather and breed in larger numbers and, therefore, tend to form bigger groups with multiple pairs. Conversely, during the non-breeding season, the size and organization of the flock varies considerably between smaller groups, which form pairs or families, to larger herds, which, in some cases, includes many outsiders. There are some species, however, that live alone and never form a flock.

There must be a reason as to why flocks, or, an ” assembly of birds”, form. If there were no merits to forming a flock, living alone could be more convenient (i.e., by being able to monopolize resource such as food). The main reason to form a flock is to defend against predators. With numbers, it becomes easier to find predators and drive them away, and to decreases the probability of being targeted. The second reason is foraging. Multiple birds can handle larger prey, and, with numbers, food sources become easier to find. The third reason would be the chance to obtain a mate or useful information. During the breeding season, birds naturally form in pairs and families.

In this work, two Japanese Robins are perching upon a blooming yamazakura tree (a cherry blossom variant). The Japanese Robin (body length 14cm) is a small and iconic bird that, alongside the Japanese Bush Warbler and the Blue-and-white Flycatcher, is named one of Japan’s three songbirds. They breed in the forests of Japanese archipelagos and southern Sakhalin and many winter in southern China. Japanese Robins are very close relatives to the Ryukyu Robin, which headlined the 24th volume of this series, and the scientific name of both species were famously reversed when the two were newly discovered. Their face and tail are bright orange, their back and wings are an orange-tinted light brown, and their bellies are a dusty white. In males, the border between the orange and white sections of the chest is separated by a black line, however, with females, this boundary is blurred and without a black line. With this considered, both robins in this work are male. Similarly, in “Japanese Robin and Plums Blossoms ” (Saita Museum), Seitei depicts two evidently male robins.

How would one ornithologically interpret the pairing of two male Japanese Robins in both these works? Would there be any ecological or behavioral reason for them to be together? While ornithological accuracy has nothing to do with art, I would like to consider this situation ornithologically.

“Japanese Robin and Plums Blossoms”

Saita Museum

Since white plum blossoms and yamazakura are in bloom, the season would be early spring. As such, these birds are most likely in the middle of a “migration”, where they fly northward from a wintering ground. However, would Japanese Robins even begin to form flocks in this period? While I am unfamiliar with the migration behaviors of Japanese Robins, I have yet to come across any research that reports such cases. However, if you infer from Daurian Redstart and Red-flanked Bluetail, which share a same group and a similar ecology, Japanese Robins will live in pairs or families during the breeding season and tend to live alone during non-breeding seasons, like migration. As such, it is very unlikely for multiple birds to be together, and it is even odder for two males to be together. The spring migration period is also the start of the breeding season, so it is not unusual for males and females to begin pairing. However, other than fights, there would be no reason for males to approach one another in such a fashion (they do not seem to be fighting). In other words, ornithologically speaking, both works go completely against the natural behavior of Japanese Robins.

So why are two males depicted in this manner? Upon closer inspection, I noticed these birds in “Japanese Robin and Plums Blossoms ” share particular features. With a black spot on their chests and a split tail, both are given unnatural traits. This indicates Seitei modelled both birds after one Japanese Robin, however, it would be strange for him not to differentiate between these birds. As such, I believe Seitei did not “paint two Japanese Robins” but, rather, “painted one”. Like a series of photographs, this work depicts a Japanese Robin on a white plum blossom branch in two positions. While the white plum blossom remains static, the Japanese Robin is depicted in two movements. I am sure this is the same with “Folding Screen with Birds and Flowers” and, with this explanation, there are no ornithological contradictions. This is how I draw my conclusion on this pair of male Japanese Robins.

Author : Masao Takahashi Ph.D. (Ornithologist)

Dr. Masao Takahashi was born 1982 in Hachinohe (Aomori prefecture) and graduated from Rikkyo University’s Graduate School of Science. Dr. Takahashi specializes in behavioral ecology and the conservation of birds that inhabit farmlands and wet grasslands. Focusing on the relation between birds and art, he has participated in various museum and gallery talks.

“Pink Parakeet with Linden” the Work Headlining this Month’s Column is Now on Exhibit at…

Watanabe Seitei Brilliant Birds, Captivating Flowers

https://seitei2021.jp/english/

Dates: 2021/03/27 (Sat) to 2021/05/23 (Sun) *This Exhibition has Ended

Venue: The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts

https://www.geidai.ac.jp/museum/exhibit/current_exhibitions_en.htm

※Advance reservations are currently not required, however, depending on circumstances involving the coronavirus, details may be subject to change. As such, please check the official exhibition site for the most recent updates prior to your visit.

Address: 12-8 Ueno Park, Taito-ku, Tokyo, 110-8714

NTT Hello Dial: +81 (0)3-5777-8600

Dates: 2021/05/29 (Sat) to 2021/07/11 (Sun) *This Exhibition has Ended

Venue: Okazaki Mindscape Museum,Okazaki Art Museum

https://www.city.okazaki.lg.jp/museum/guidance/p008834b.html

Address: Okazaki Central Park,1 Aza Toge, Koryujicho, Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture 444-0002

TEL: +81 (0)564-28-5000

Dates: 2021/07/17 (Sat) to 2021/08/29 (Sun) *This Exhibition has Ended

Venue: Sano Art Museum

https://www.sanobi.or.jp/eng/index.html

Address: 1-43 Nakatamachi, Mishima, Shizuoka, 411-0838

TEL: +81 (0)55-975-7278

.jpg)